Back in 2012, marketing innovator Jonah Sachs published “Winning the Story Wars”. The book had a big impact on me and some of my colleagues. It’s directed at marketers, but the message applies to anyone in media: stories are how people understand the world, and to truly captivate an audience, your story should cast the world in clear terms of good and bad and describe the epic struggle between them. Sachs is an upright guy, so he added that your story should be true.

Facebook is currently engaged in a story war, and it’s losing. The social media platform’s story is the tech revolution bringing wonder and social connection to millions of people. It’s the rebirth story, the steady march of progress story. The opposing story from Facebook’s antagonists in the news media and political establishment is more ancient and powerful: Facebook is evil, corrupts everything it touches, and is engaged in a life-or-death struggle with the forces for good. Children and democracy are under threat. In this story as told in news media, it’s the journalists themselves who are implicitly the “forces for good”.

To be clear here: Sachs’ theory is about a contest of narratives. In this contest, the side with the better narrative wins. The better narrative is the one that resonates more deeply, is easier to understand, and accords better with peoples’ beliefs, desires and fears. The winner’s story appeals to both those who tell and those who listen to it, and it’s heard more often.

For the past five years, news articles written about Facebook have increasingly come from the “good versus evil” narrative. The past two weeks have marked a high point, or a low point depending on your perspective, and now every piece of news we read or hear about Facebook is about its harmfulness or duplicity. Two weeks ago The Wall Street Journal ran a five-part series using leaked internal documents, and at the weekend the former employee who leaked those documents was interviewed on 60 Minutes in the US.

The exaggeration machine

While Sachs was careful to include truth as a marketing requirement, it’s not at all clear that truth is necessary for success in the story wars. In fact, exaggerations, half truths, and lies seem to have an evolutionary advantage over truth in the short term: they are cheap, easy to understand, and can be perfectly adapted to their own transmission.

Facebook does have big problems. It is incentivised to maximise engagement, and it turns out that maximising engagement is not good for users, who incidentally, are not its customers. It’s that old devil, the advertising model, raising its two-faced head. In a classic agency problem, the people who use Facebook do not pay Facebook. There’s a misalignment of incentives as Facebook balances the best possible product for advertisers with the need to engage users.

In algorithmically maximising engagement, Facebook facilitates and benefits from stories that fit the ancient templates. Exaggerations, superstitions, lies and other forms of disinformation prosper because they are usually cheaper to create, more interesting, easier to understand, and more memorable than accurate accounts. In other words, Facebook benefits from the story war dynamic within its platform for exactly the same reason it is losing the story war at the macro level.

The middle truth

It is possible to recognise the defects and hubris of Facebook without falling into exaggeration and caricature. An example of the latter is the suggestion the social network is analogous to the tobacco industry. Facebook does not kill half its users. It’s a bad analogy.

At the same time that current coverage is overblown, it underplays significant aspects of the problems with Facebook. Many of the deepest issues, such as the vulnerability of “the human operating system” to exploitation, may well be universal within digitally mediated networks, which means we can’t afford to see this as a one-company problem.

It’s worth noting here that the news media itself often exploits the same human weaknesses and tendencies as social media. Exaggeration, the nurture and amplification of anxiety, and the promotion of social and political division have been surefire ways of selling newspapers and generating traffic.

Why The Wall Street Journal landed the blow

This brings us back to the story war. The reason the WSJ leaks have made such a big impact is not so much the explosiveness of the material as their perfect fit within the “good versus evil” narrative. Reviewing the WSJ articles and the interview of whistleblower Frances Haugen, no one came at the material with an open mind.

Some commentators have noticed this. Benedict Evans, for example, wrote in his newsletter that excerpts from the documents were “all carefully quoted with a presumption of bad faith”.

This is not significant in the big picture. My experience of newsrooms is that journalists, including myself, employ something like the opposite of the scientific method. Instead of attempting to disprove a hypothesis, we will bend over backwards to “stand up a story”.

What is important is why the WSJ journalists came at the story like that in the first place, and why editors all over the world picked it and ran with it without a moment’s hesitation.

I could speculate on a few causes. Firstly, the business and editorial interests of news media align with “good versus evil” story. Back in 2018, Facebook made an algorithm change that badly affected news media using the social network as a distribution channel. This was widely seen as a breach of faith, and soured a relationship that had been been going bad for years. The media had collectively begun to believe that Facebook and Google – rather than the internet in general – had destroyed their business model. It is so much easier to understand an embodied enemy.

The other important element is that journalists, on a personal level, are addicted to the “good versus evil” story. Anyone who has worked in a newsroom knows this. The chance to be the hero in a monumental and important struggle is a powerful motivator.

The way home for Facebook is boring

Facebook has come out strongly against the WSJ allegations and revelations. It has pointed out the studies quoted were not representative, were not designed to get at objective levels of harm, and read the way they do because the people who made them were tasked specifically with rooting out harm.

CEO Mark Zuckerberg has correctly identified that – because the criticisms arise from research the company itself commissioned – Facebook is now incentivised to shut research down and learn less about the effects of the social network on its users. He says he won’t let that happen.

The problem is, no one outside Facebook cares about the rebuttals, and continuing research will actually just make the story more and more interesting. Few people in media are sitting back and weighing up the evidence. The story of good versus evil has momentum beyond reason.

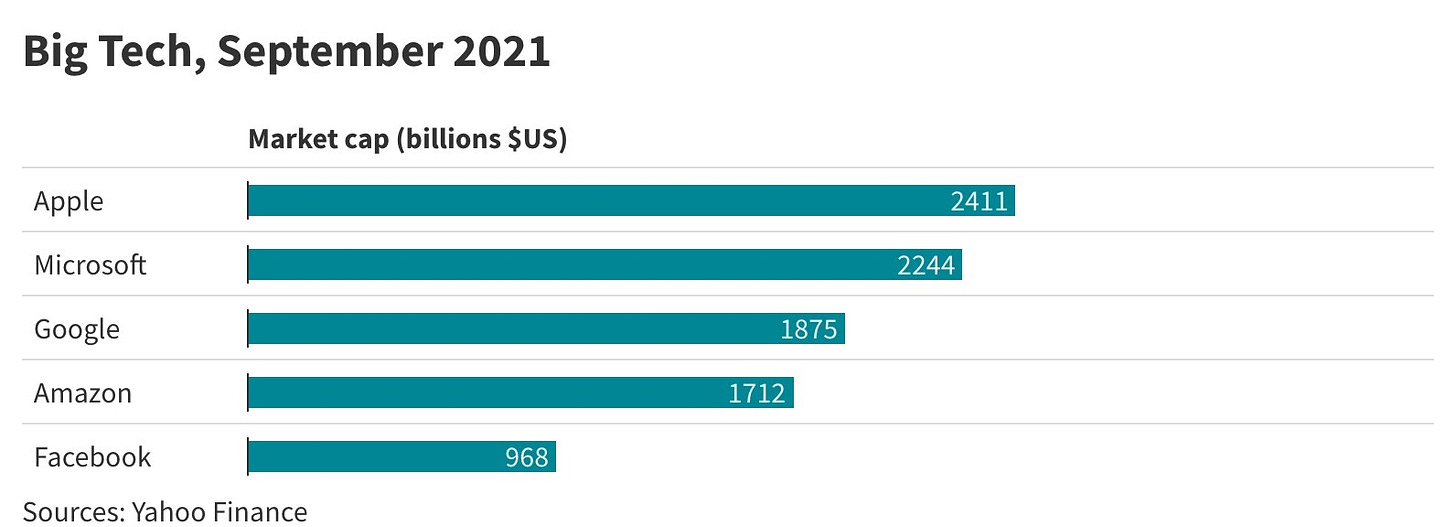

It’s fascinating to observe how companies move through life stages. Microsoft was once a victim of the story wars, just as Facebook is now. Consider the recent market caps of Big Tech (table reproduced from my opinion piece in The Spinoff):

Microsoft is more than twice the size of Facebook, and it cops a fraction of the animosity. One of the reasons is that it is a lot more boring.

In corporate terms, it’s dangerous to be as interesting as Facebook is right now. If Facebook appears on the above leaderboard in a decade’s time, it will be because it has learned that lesson and built an alternative templated story (for example, the prodigal son) that news media can mostly ignore.

Stand by for Jonah Sachs’ thoughts on the Facebook vs Everyone story war. Sachs has agreed to an interview, and I’ll be fascinated to get his take on this battle.

If you don’t subscribe to Crawford Media, please sign up!