When it comes to news output – as opposed to newsrooms – I’ve always known that appearances are important. The visual design, the presentation of news, is a language in itself, full of meaning and indicative of the care with which the news has been created.

The story behind the Crawford Media logo design is one that means a lot to me.

If you are not a subscriber already, please consider signing up.

First Person: How to make a logo

In early 2016, Iris and I faced a big decision: move the family from Sydney to Auckland for my opportunity to run a big broadcast newsroom, or remain at ninemsn. Ninemsn, an old-fashioned digital portal, was being incorporated fully into Nine at the time, having been created as a joint venture with Microsoft in the early days of the internet.

In evaluating the opportunity in New Zealand, I was heavily influenced by something the people at Mediaworks had cooked up: Newshub. This brand was inspired, I could see it had the flexibility to cover a big online expansion, bring continuity to TV and radio, and allow for new developments like events. And it was sharp. The sans-serif, flat and clean look was a world away from the Nine TV aesthetic that I was getting sucked into.

I later found out who was responsible for the Newshub design: creative director Ant Farac. Head of news graphics James Brown also had a lot to do with the design execution and studio sets.

So I took the job as Chief News Officer at Mediaworks. It was a daunting move. I didn’t know how to make TV, I wasn’t a Kiwi, and I was leading a team of close to 300 people. I wasted some energy dreading exposure as an imposter. But you’d be surprised how little people expect of their bosses. I tried hard, and kept trying. The cliche is right: the important thing is to keep trying.

Moving into a new job is like moving into a new house. You spend a lot of time wondering what on earth the previous occupants were thinking. I now understand the quirky genius of my predecessor Mark Jennings – he lasted more than two decades at the place – but at the time I questioned some of his decisions. One of the first things I changed was the relative standing of the news graphics department, tweaking the hierarchy so that James Brown reported directly to me.

I could tell straight away that James was someone special. A big guy, he spoke softly, with a kind of gentleness and intensity. He was passionate about design, he was passionate about his team. “I’m from Niue,” he told me, and I had no idea where that was.

One day I discovered James was a fisherman, and we arranged to meet at a jetty in the far north of Auckland on a weekend morning. It was dark, an eerie scene, casting lines out into the the black water. James had brought a ridiculous amount of bait – 5kg of pilchards – and we stood there as the sun rose, making parabolas with our lines, feeling the bites and landing undersized snapper. The fish went back into the water, but we made a competition of the numbers. I felt like I was back in Perth with my brother. The bait was gone.

From then on, James and I went fishing often. Together we took up kayaking and explored the islands of the Hauraki Gulf. Even at the time I felt like I was in some kind of Boy’s Own Annual. The sense of possibility, paddling out into the sunrise, islands dotting the horizon, fish, sharks and shipwrecks in the offing: these are things I will never forget.

Along the way James told me stories about Niue, and I became so intrigued we booked a family holiday there. You fly over hundreds of kilometres of open ocean and there it is, a rocky island in the middle of the Pacific, with sheer cliffs and almost no beaches. If the roads were good, you would be able to drive around Niue in an hour. The roads aren’t good. Only 1600 people live there and the infrastructure is pretty rough. I visited James’ old house and the wharf his dad built, I fished from the reef and watched the mid-ocean swell rise fast from the deep water and smash the land. There’s nothing between you and the horizon. The water shows off its colours: transparent at the shore, clear teal over the reef before the dark blue of the kilometres-deep ocean.

James and I talked about work, management philosophies, tech innovations and pretty much anything. James speaks with quiet authority, and you’re never sure when he’s going to challenge you. I don’t know if that’s a Niue thing or a James thing. Wherever it comes from, his ability to contradict without conflict is a gift.

Eventually James decided to leave Mediaworks. He’d had enough of the stress, the cost management, trying to keep his young staff from straying. In his leaving speech he told the story of the time we took a short cut through thick bush to get to a fishing spot south-east of Auckland. We became lost, stuck on a precipitous slope above a lethal cliff. Somehow the simplest excursion had progressed with each poor decision until we had manufactured a life-or-death situation. James slipped and smashed his glasses. The bait bucket I was carrying escaped my hand and disappeared over the cliff edge. It was ludicrous.

We advised each other to remain still and breathe.

There came a moment when Iris and I had to make another choice. We’d been renting in Auckland for more than two years, always with the idea that we might one day return to Australia. Would we go all in on New Zealand, or return? I was sick of never putting down roots, never fully committing. By the time we returned to Australia with a container full of stuff and an Auckland rescue dog, three and a half years had elapsed.

I started consulting and writing, was advised to use my own name for the business, and made a logo. I can use Photoshop and have a sense of visual balance. I sat with that logo for about a month before I realised it wasn’t good enough. It was amateur hour. So I called James.

“When you’re working through the design, you look at the page and wait for something to speak to you. For me it’s important to find out about the client. What’s their style, what do they do outside of work? Where do they drink, what kind of restaurant do they go to?”

I didn’t give James a brief. I didn’t have to. Shared experience is the foundation of understanding. That’s the problem with remote working, remote being. It stands in place of true shared experience, and it’s a poor substitute. James and I were disposed to understand each other from the beginning, but the jetty, the island, the cliff in the thicket: these things go beyond surface acquaintance.

A week after I asked James for help, he came back with a brand and creative document that I loved. There was no need for alteration. James had understood my brief better than me.

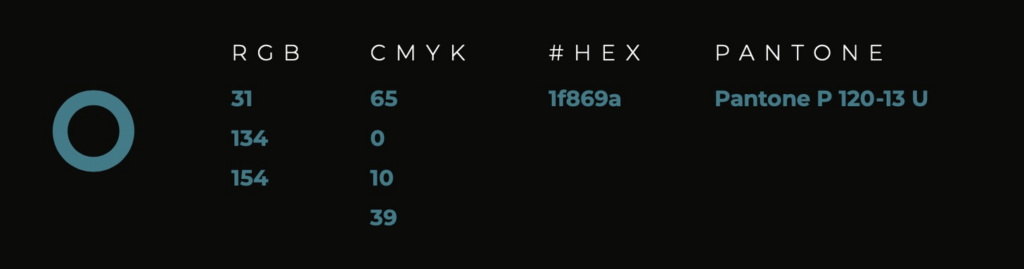

“I’ve always liked the colour teal. For you and me both, I think. It’s the colour of the ocean.”

He says the round, continuous lines of the logo were inspired by the Circulon brand of cookware and the need to represent the “CMC” business initials.

When I ask him about the design development, James is candid. He laughs as he reveals secrets most designers would have purged from their hard disks.

“You might be quite horrified when you see this,” he says, and sends through a PNG of a boxing kangaroo-style green-and-gold design (see above). There follow designs reminiscent of Malaysian Airlines and something that smacks of a superhero cat.

“You have to go through the motions. Is this you? I basically threw everything out.”

After James left Mediaworks, he started up Browns Collective. It’s a group of designers and creatives James has drawn together to provide clients with a one-stop shop. While they take a coordinated approach to design, everyone in the collective works for themselves.

James says attitudes towards design are changing.

“You feel the effects, post-COVID, of what I call vanilla design, click-and-collect design. People are going to sites like Logo Maker or Wix and making stuff for the person up the road. They don’t appreciate what goes into a fully-fledged brand.”

I have learned a lot from James. On the eerie jetty he taught me how to cast properly. How to contradict someone well. That if you want to know someone, you have to do something together. And that somehow you have to realise your own take on the world isn’t all there is.

“You only know what you know, until someone else comes along,” he says.

I guess I am lucky that James knows what he knows, and that I know James.