Analyst Benedict Evans has built a global following understanding and explaining how tech is transforming the world, and this week I had the opportunity to talk to him specifically about the business of news.

I know Evans through his insightful and wide-ranging Benedict’s Newsletter, and in person he turns out to be intense, fast-talking and dismissive of news exceptionalism: the idea that news is a different kind of business than everything else.

Evans is no futurist or corporate huckster. The former partner at venture capitalist Andreessen Horowitz speaks to 160,000 people every week through the newsletter, with many of his subscribers based in Silicon Valley (30,000 subs there) or other high-tech and high-influence environments.

This post will deal with the main themes from the interview, and as with my Tim Burrowes conversation, I will publish a podcast in a few days.

Wayback perspective

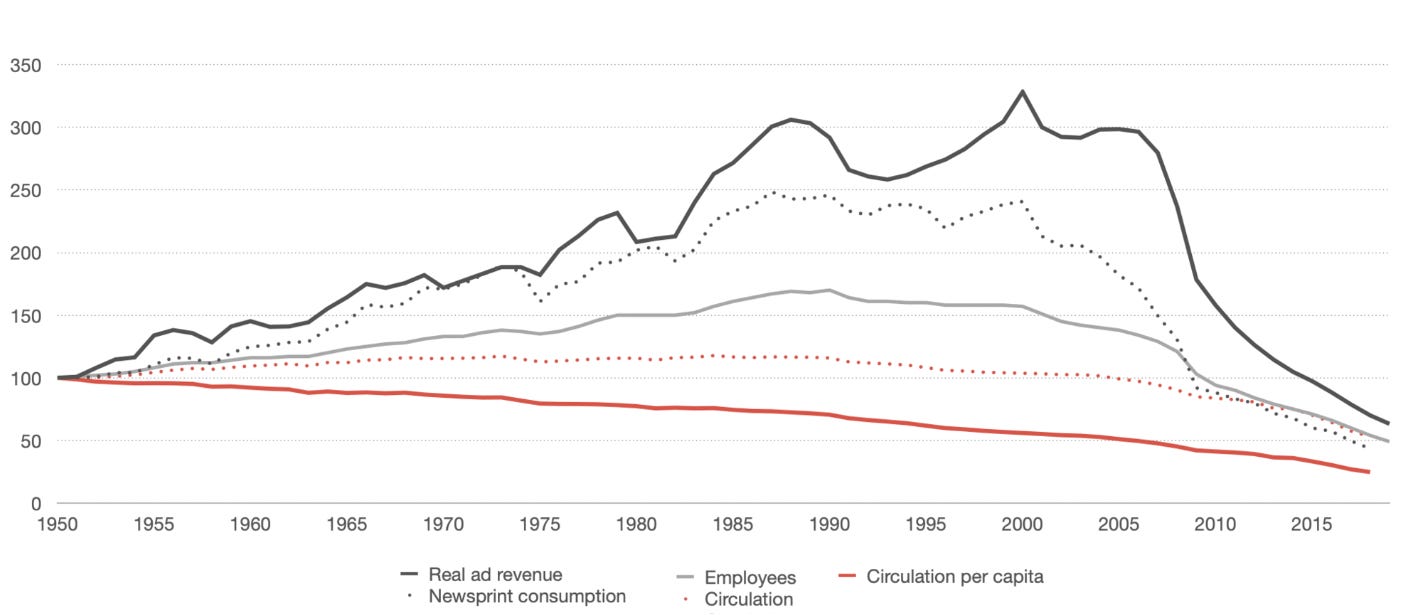

Evans, a Cambridge history graduate, often contextualises his analysis in terms of centuries. In the case of news, he has painstakingly compiled a graph of US newspaper revenue, circulation and employment from 1950 to the present day. What it shows is that circulation per capita has been declining for 70 years.

“One of the interesting things about that chart … the newspaper that we had in 1995 was not the natural, eternal order of things. It was already a newspaper industry that looked radically different from the industry of 1950, or of 1930.”

On Evans’ telling, the reaction to this shrinking readership was to move up-market, expand page counts, add supplements and hire a lot of journalists to write new kinds of content (features, investigations) in order to increase ad inventory.

“Then of course, the internet comes along .. on the one hand, the advertising opportunities for advertisers just got completely transformed. And the other hand, the things that your audience were reading got completely transformed.”

“To look at this and say, ‘Well, we used to all have all this money and now Google has got it’, it’s just idiotic. It’s as though you’re an ocean liner company and you’re saying, ‘Boeing stole all our money’. That’s not really what happened.”

If you are enjoying Crawford Media and don’t subscribe, please sign up. It’s free.

Wrongheaded legislation

Given Evans’ big picture analysis, it is no surprise that he is opposed to legislation like the Australian News Media Bargaining Code that has forced Google and Facebook into big payments to news publishers. The estimated value of deals signed under the influence of the code is A$500m over five years.

“If you’re going to construct a funding mechanism for any part of society, really that funding mechanism should be sustainable and it should be based on some sort of coherent logic. It should be intellectually defensible. It shouldn’t really be based on an argument that disintegrates as soon as anybody asks any questions.”

He points to problems with the code, and to similar regulation being implemented globally. The first objection is that no one on the internet pays to link to anyone else’s content, regardless of the linker’s market power. The second is that if news companies are owed money for Facebook and Google linking to their content, then other content creators are too, and that would bankrupt the platforms.

I agree. But do the ends justify the means, in terms of getting money flowing to news publishers?

“It’s an argument that presumes that somehow news should be treated differently, which is a perfectly legitimate, moral position to take, but it’s not a business position or a competition question. It’s a subsidy question.”

Evans says financing public interest journalism is an important issue that must be solved with a straightforward approach.

“How do we pay for public service journalism? Well, I think a good starting point has to be to say that you’re asking for a subsidy.”

The problem with subscriptions

Subscriptions have worked for the really big news brands, like The New York Times, and for niche prestige publications like The Economist, but Evans says that general mid-tier news is being “squeezed out”.

“Subscription works for a certain kind of title. The challenge for everybody else trying to do it now, is that I’ll take two or three [subs] of the strongest brands, but I won’t take 10.”

Then at very low scale there are newsletters.

“One of the interesting things about newsletters is that somehow paying for one person’s blog doesn’t work, but paying for more or less exactly the same thing by email does.”

“You’ve shifted the psychology or the value proposition somehow. My theory is that when you’re getting a tangible thing in your inbox every week or every day, that has more value than the same thing appearing on a website that you might or might not remember to visit.”

He’s sceptical of micropayments for news, if only because they have been tried and failed so many times.

“There’s something there, but it’s a lot harder than it sounds.”

Breaking up, coming together

Evans deals with the big forces at work in the world of content and tech. He’s done time in Silicon Valley, and his stock-in-trade is spotting flaws and strengths in business models. One of his analytical tools is the now well-known “bundling/unbundling”, a concept from Netscape pioneer Jim Barksdale, who said “there’s only two ways I know of to make money: bundling and unbundling.”

Evans refers to Instagram having “unbundled” magazines, by allowing audiences to access glossy photography and personalities directly. But there are opportunities in “re-bundling” as well, in terms of bringing audiences and content together in new ways.

“I think one of the things that’s sort of happened recurrently over the last 20 years is a sort of aggregation/dis-aggregation of people creating ideas, content analysis, writing, whatever it is.”

He points to an opportunity for newsletter platform Substack (which this newsletter uses) in terms of bundling different writers in some way.

“Substack is a bundling story. Today, yes there’s a leaderboard on the homepage, but it’s not really a consumer-facing brand. But clearly if they were to reach a point where they had millions of people subscribing to thousands and thousands of different newsletters on the platform, then they could look at what you’re reading and suggest other things … then Substack would be an aggregation layer … and a reason to be on Substack [as a writer] would be that they would get you more readers.”

The cycle of deriving value from splitting up or aggregating content is constant. This calls to mind a possibility that seems remote but interesting to me: whether Netflix would ever consider getting into news, given that news is high-engagement video and Netflix is so hungry for content.

Evans runs through objections to the idea, then gets down to the nitty gritty.

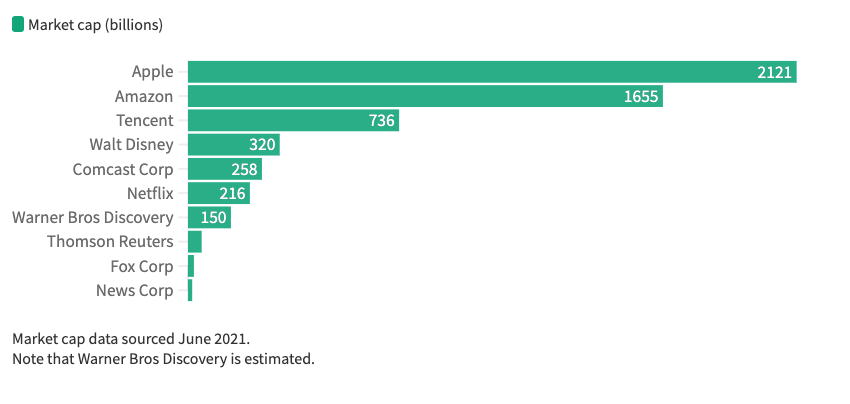

“You know, people in the newspaper industry sometimes give the impression that they think everyone in Silicon valley is obsessed with them. They’re really not. News is small. In economic terms and in time-spent terms, news is not an important industry. It’s socially and politically important, but the money is not important.”

Benedict’s verdict

I’m not put out by Evan’s brutal assessment: actually, I think he’s mostly right. News is self-absorbed and financially insignificant compared to the corporate giants. If you doubt that, have a look at the graph below. I made it for a piece on The Spinoff last month. The Thomson Reuters, Fox Corp, and News Corp bars were too small to carry numbers.

But while the money may be small, the social and political heft of news is big, as Evans acknowledges. And that counts for a lot, particularly in an era where the regulation of the internet is going to progress and intensify. The News Bargaining Code may be “grubby”, as Tim Burrowes commented last week, but it is also a great demonstration of how political power works. Poor arguments and naked self-interest are no impediment to laws aligned with the zeitgeist.

The move to regulation is one of the big trends Evans is talking and writing about at the moment, and if you do not already subscribe to his newsletter, I recommend you sign up. For anyone whose heart belongs to news, he is a provocateur, and when it comes to the media business we need more of that.

Podcast preview

Have a listen to the podcast of this interview for more detail on:

- How the ad business has fundamentally changed

- The coming wave of regulation

- More on micropayments