Around the world, democracies are waking up to a market failure in news.

We’ve been talking about it for more than a decade.

Now things are starting to happen. Governments are becoming involved in financing public interest journalism. This will become one of the big picture developments in news, the kind of development that marks an era.

News is not dead, but it’s half the person it used to be

Late last year I was employed by funding agency NZ On Air and the NZ government to put in some groundwork on public interest journalism. Jacinda Ardern’s newly re-elected government had more than $50 million to spend on news over three years, and they wanted to canvas views on how to do that.

I started the job without assumptions. I wasn’t ready to agree that news was in decline. I’d rather believe that people are still getting the information they need through other channels.

But the data I gathered about the New Zealand market was convincing and multifaceted. Whether from government, education or industry, the figures all pointed to the same conclusion: collapse. The number of people working in Kiwi news media has halved over the past 15 years. News article output has dived and interest in journalism education is the lowest it has been in at least 20 years.

These numbers go beyond anecdotes from journalists and editors. I received much of the data confidentially and can’t share it here. I saw year-by-year breakdowns of employed journalists and article outputs for one big publisher. Applications to journalism courses – rather than actual student numbers – were for me perhaps the most damning indictment of the health of the news ecosystem. Very few young people are hearing or heeding the call. Half the NZ tertiary courses have closed and the other half are struggling.

A global trend

The next step was to look around the world and see how other nations were dealing with news output decline. It was interesting to see programmes reflecting to some extent the national character and culture.

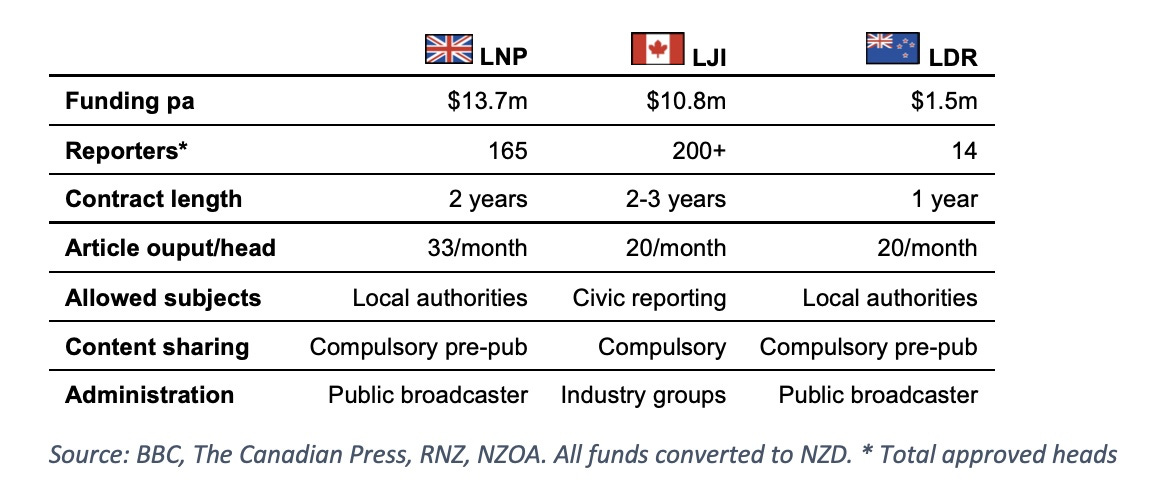

One big initiative is the UK’s Local News Partnerships (LNP), a programme run by the BBC whose major pillar is the employment of more than 150 reporters through local news outlets. As the name implies, it’s a partnership between the BBC and small commercial newsrooms, and it’s restricted to reporting on local government authorities.

The Canadians are more prolific and less strict with their Local Journalism Initiative (LJI): they have employed more than 200 full- and part-time local reporters to cover local news that may include colour pieces and features. The LJI is governed by an industry working group.

In the table below (taken from the final PIJF report) I’ve compared these programmes to the NZ LDR, a small-scale local reporting initiative already underway in NZ when I began my report.

The US doesn’t yet seem to have an equivalent to these local news programmes, and favours philanthropy rather than the public purse. ProPublica, for example, employs over 100 reporters, costs $30m USD a year to run and is largely financed by big donors. I think reliance on philanthropists comes with problems for journalism. This, along with the risks of governments funding news, is something to explore in future newsletters.

While these programmes were being set up, the Australian government dedicated a great deal of energy to the News Media Bargaining Code. This law forcing Facebook and Google to help finance news in Australia is flawed on several levels, but perhaps its biggest fault is that the money doesn’t have to be spent on making news. Deals are opaque and contain in-kind payment. It is a non-starter in global public interest journalism terms.

To be fair to Australia, there has also been the Public Interest News Gathering Fund – set up as a COVID relief measure – which handed out $53m to support regional news in one big sugar hit late last year. But the PING isn’t a PIJ funding strategy by any means, and there doesn’t seem to be a great deal of transparency around what the money has been used for. Most of the money has gone to 10 organisations (see Who got Public Interest News Gathering money?).

My survey of public news financing was far from exhaustive and focussed on the most accessible and instructive examples: those in the English-speaking world and those concerned with local reporting. There are myriad think-tanks, institutes and programmes focussed on this problem worldwide.

Making the money work

The final step for me was to write the report, summarising the views of the industry and making recommendations about the structure of the fund. This work formed the basis for NZ On Air’s Public Interest Journalism Fund, which opened for applications at the end of April. They worked hell-for-leather to get this live in such a short time.

The way the fund works is sensible and efficient. It has retained NZ On Air’s basic system of assessing and funding in rounds. There are three pillars within the fund, one for news projects, one for funding reporting roles, and one for industry development and training. About $10m NZD will be approved within this financial year, with the fund getting into full swing next financial year, when it will distribute $25m NZD.

It’s worth noting the scale here. My expectations are that the role-based part of the fund will see the employment of at least 100 reporters, and the investment in training and projects has the potential to re-start the pipeline of talent into NZ journalism. This for a nation with a smaller population than Sydney. In absolute per annum spend the PIJF, as it is now known, will be bigger than both the British and the Canadian local new programmes.

Not just funding public broadcasters

The PIJF is limited to three years, but my hope is that the funding structure will prove effective and lead the way in publicly funded reporting. This is a crucial experiment. Critics may ask why the money cannot simply be given to public broadcasters. While public broadcasters are evolving into “public newsrooms” with high news article output, and have a big role to play in the future of news, they represent too narrow a range to be the sole support for PIJ. We need a diversity of voices and we are not going to get that by simply handing more money to the BBC, CBC, ABC or RNZ.

There will inevitably be criticism of PIJ funding schemes from those who miss out on the money, or from critics who see them as props for failing businesses. The NZ government and its agencies will have to brace for that. If the fund retains a focus on audiences and news outputs, rather than the needs of industry, it can avoid a host of problems and inefficiencies.

Sign up for the Crawford Media newsletter to get more articles like this direct to your inbox weekly.